While ocean warming and coral bleaching events make the headlines around the globe, there’s a team of pioneering marine researchers quietly working on new methods to rebuild coral populations more resilient to rising temperatures through groundbreaking means. And it’s all happening in Cuba.

22/07/2025 Written by Ryan Green — Oceanographic Magazine

Photography by Zach Ransom & Ryan Green

It’s the middle of the night. The sky is dusty white with stars, so many that it’s difficult to distinguish one from another. The full moon hangs low above the ocean’s inky surface and creatures scuttle across the seafloor. Stripy lionfish dance their poisonous dance, fins fanned in dazzling display. And throughout the intricate passageways of an extensive reef, corals get ready to spawn.

Each August, under the cover of darkness, a species of coral at Playa el Coral – off the northern coast of Cuba – releases a cloud of eggs and sperm. The underwater world comes to mirror the sky above, the sea sprinkled with millions of microscopic particles.

Coral species reproduce either through “brooding” or “broadcasting.” The former release fully fertilised juveniles; the others, called broadcast spawners, release sperm and eggs separately. If all goes well, somewhere in the vast water column, a tiny sperm and egg will find each other.

If by a moon dance miracle, the two gametes do connect, they become a planula, or coral larvae. They are carried by currents or settle on the reef below, trying to beat the odds: only 1% of corals survive their first year of life.

Along the two square kilometres of Playa el Coral, hundreds of species reproduce this way: the vibrant purple fan coral, the branching orange elkhorn, and the boulder star coral that encrusts rocks in tiny green polka dots. The scientists and divers who know this spot well all agree: it is one of the healthiest reefs in the Caribbean, if not the world.

Many narratives about coral reefs are centred on bleaching, death, and extinction. Which is, for the most part, accurate. According to the World Economic Forum, 14% of reefs have been lost since 2009. In Australia, over 70% of the Great Barrier Reef has bleached. In Florida, 90% of the reefs – stretching some 350 miles – have disappeared in just the past 40 years.

Many things contribute to reef loss: overfishing and trawling, destructive tourism practices, and pathogens like stony coral tissue loss disease. The biggest threat facing corals, however, is climate change-induced marine heat waves. This type of oceanic warming causes corals to bleach, a process that can end in fatality.

“We have a serious extinction risk for many of these corals,” said Margaret Miller, who works for SECORE International, a non-profit that specialises in coral restoration.

Most of the planet’s over 100,000 square miles of reef are concentrated around the equator, where, for millions of years, corals have historically been happiest. This is mostly because temperature and light conditions were just right for their survival and reproduction. (A few cold water corals are the rare exception.) But the earth’s tropics are growing increasingly inhospitable for the over 6,000 known species of coral.

Corals are animals, communal organisms made up of individuals called polyps, living together in a colony. The foundation of these colonies is the corals’ skeleton, made primarily of calcium carbonate. Covering this limestone skeleton is their tissue, which includes not just coral polyps, but symbiotic algae, roommates of sort, without which the coral could not survive.

These algae, which are called zooxanthellae, provide valuable, life-giving nutrients to the coral. The algae also give coral their colors: without them, the polyps would appear white.

When ocean temperatures get too warm – sometimes by just 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius) – corals become stressed and expel the symbionts that sustain them, exposing the ghost white skeleton beneath through their transparent tissue. Bleached coral doesn’t necessarily mean dead coral, but often, bleaching can be the first step towards mortality.

In 2023, the Caribbean Sea broke records with the average temperature staying above 66 degrees Fahrenheit – 19 degrees Celsius – for nearly two months. This is well above the 20th century average of 57 degrees Fahrenheit (13.9 degrees Celsius). This February, news came from western Australia about a severe bleaching event on the Ningaloo reef, where divers and scientists alike were shocked by water temperatures that skyrocketed above 120 degrees Fahrenheit, roughly 50 degrees Celsius.

In both places, vast stretches of coral bleached and then died. Their limestone foundations became vulnerable to overgrowth by seaweed, a sure sign that a coral is dead. Engulfed in a fuzzy shock of algae, these corals won’t regrow. Instead, they will turn to rubble, piling up in dark mounds on the ocean floor.

Many things contribute to reef loss: overfishing, destructive tourism, and pathogens like stony coral tissue loss disease. But the biggest threat is climate change.

Marine biologist Fernando Bretos remembers the first time he saw coral, more than three decades ago, in the Florida Keys. As a teenager, he was awestruck by the underwater world. He recalls how the tissue of pillar coral, a species now facing extinction, was almost fluffy in appearance, jutting up from the seafloor in cylindrical shoots like small buildings, part of a miniature underwater city.

He was smitten. But when Bretos returned to Florida’s Pennekamp State Park in 2018, what he discovered was shocking. “Everything was rubble,” he said. “I could only see their skeletons,” said Bretos of the brain coral that had been thriving there just six months before.

In early 2019, Bretos traveled to Cuba, the island from which his parents had fled decades earlier. Travel to Cuba had become a regular part of his professional life, but this time he carted curious cargo: three suitcases, each filled with ceramic disks wrapped tightly in newspaper inside cardboard boxes.

Scientists and innovators are devising ways to protect coral ecosystems in the warming oceans. The projects range from land-based, Noah’s Arc-style coral seed banks to immense geo-engineering projects. The majority of these methods fall into two main categories: asexual reproduction or assisted sexual reproduction.

Asexual reproduction is more commonly known as fragmentation. Researchers break small bits of coral off a large colony, care for them while they grow larger, and then affix them to an unhealthy or sparse part of the reef. But the coral fragments, which are genetic clones, are no better at surviving warmer waters than their parents – there is no genetic mixing that might introduce a climate adaptation.

Bretos notes that the approach is much more widespread than assisted sexual reproduction; “for every sexual propagation project, there’s a hundred fragmentation ones,” he said.

The second approach – assisted sexual reproduction, that the team is attempting in Cuba – offers that very possibility. This method is based on what corals do naturally – on what can be seen each August along the expanse of the Playa el Coral reef as broadcasting corals send out their gametes. Ideally, a coral sperm and egg from two separate colonies, or a different reef altogether, meet and grow into an adult coral. But in this method, scientists are facilitating this early connection. The offspring is thus a genetic combination of its parents, one of which may have an adaptation that allows it to survive increasingly warm environments.

To Miller, the approach makes the most sense right now. “Restoring successful sexual reproduction on coral reefs is just a prerequisite for them to ever be able to adapt and regain a self-sufficient, sustainable status,” she said.

In a recent paper in the journal PLoS, Miller and twelve colleagues showed that corals from assisted sexual reproduction experiments showed more tolerance to the 2023 Caribbean marine heatwave than individuals derived from fragmentation – asexual reproduction – or than naturally occurring corals of the same species. This means that baby corals born from the assisted sexual reproduction method were more resilient than all the others to the main threat they face: oceanic warming.

Bretos and a small team have been piloting this method in Cuba. It is no secret that Cuba presents logistical difficulties, especially for Americans. An economic crisis has been left in the wake of the Cuban Revolution and ensuing U.S. embargo. Access is hard, funding for projects is scarce, and politics entrench even the smallest of decisions.

Due to permitting hurdles, Cuba couldn’t be included as one of the fifteen sites in the PLoS study. But with support from the Caribbean Biodiversity Fund and SECORE international, Bretos and the Cuban team are rolling out the method along the island’s shores. And a key piece of this project is ceramics… and suitcases.

“This is a hope story. This is not a ‘look what we’ve done’ this is a ‘look what we’re doing.’”

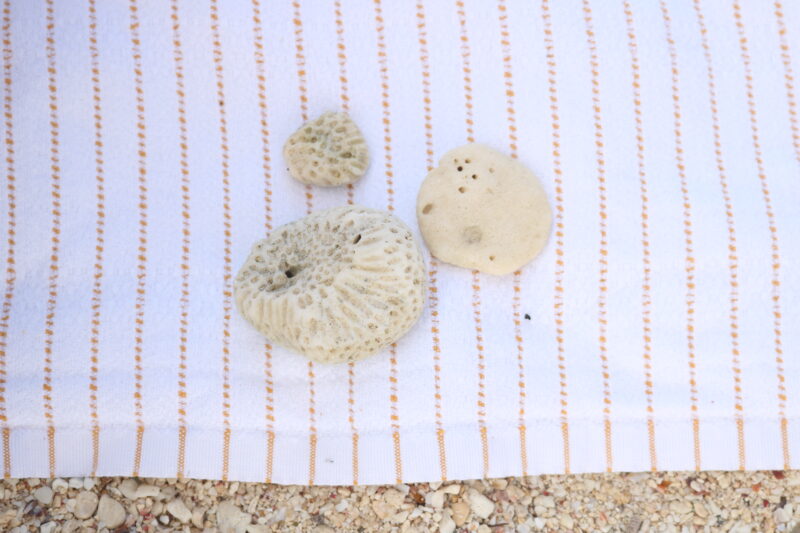

Mara Haseltine, an artist and nature-based designer, met Bretos in 2021 and learned that he had, in three trips, lugged 11,000 ceramic discs to Cuba for a coral restoration project. The pale white ceramics, about three inches in diameter, provided a surface for the baby corals to grow on.

Haseltine wasn’t sure how, but she knew she wanted to help Bretos with his coral substrate supply problem. She decided that she wanted to make the homes for the tiny coral larvae into works of art – and that she wanted the ceramics to be produced in Cuba, providing income for artisans there.

Haseltine knows art and she knows science. What she didn’t know was Cuba. So she was introduced to Israel Dominguez, a Babalawo, or priest, of Santería, the most widely practiced religion in Cuba. Though Dominguez is a public person, he’s also soft-spoken, and Haseltine slowly earned his trust through a series of meetings. “She wanted to understand our culture,” said Dominguez. The pair spent days together, designing estrellas del oceano, or stars of the ocean.

The small, palm-sized sculptures that will host the coral larvae are intricate and sea-star shaped. On the bottom are the images that Haseltine and Dominguez settled on: corals spawning, their gametes drifting to the centre of the star, where the hands of Yemaja, the goddess of water, lift them up. Between Yemaja’s hands: the words “Hecho en Cuba,” meaning “made in Cuba.” All this below a full moon, the coral’s secret signal that it’s time to spawn.

The first two sites Bretos and the team chose for the restoration project are Jardines de la Reina off the south coast and a bay off the Guanahacabibes peninsula, to the southwest. Playa el Coral and Jardines del Rey will be next. Bretos hopes to use Haseltine’s stars for the gametes from Playa el Coral.

Assisted sexual reproduction requires much more time than fragmentation does. When Acropora coral spawn in August or, sometimes, September, divers cover the parent colonies with a fine mesh net that allows only water to pass through. The tapered end of the net funnels into a small glass jar where the coral’s broadcast is caught. If all has gone well, this mixture of eggs, sperm, and seawater is collected from the reef.

The divers then deliver the baby corals to labs or the aptly named Coral Rearing In-situ Basins (CRIBs). These floating blue hexagons “look like bounce houses,” said Bretos. The ceramic substrates rest inside these inflatable labs, about a foot below the surface of the water, on nets suspended between the two sides.

Inside the CRIBs, jars of larvae are poured over the substrates. Many young gametes fall to the ocean floor. But some land successfully on the substrates, protected from the fish and other predators that feed on coral spawn. Once the planulae have grown big enough to make a go of it on their own, divers place them on the reefs. Often wedged in a crevice or nearby other, older coral, the new, genetically diverse juveniles begin what the team hopes will be long lives.

Cuba has made significant efforts to protect their seas, establishing marine protected areas safeguarding 25% of their ocean.

Cuba’s corals are, for now, doing better than many of their neighbouring Caribbean reefs. Because tourism in Cuba has been limited, little damage has come from cruise ship pollution, waste dumping, and anchor dragging – or from tourists standing on or damaging the corals.

Cuba has also made significant efforts to protect their seas, establishing marine protected areas safeguarding 25% of their ocean, according to the Nature Conservancy.

However, the rate of coral loss in Cuba vastly outpaces the restoration efforts at the two initial sites: Guanahacabibes and Jardines de la Reina. At Jardines de la Reina, due in part to the isolated location of the site and faltering funding, the baby corals are not coming back.

During the global marine heatwave of 2023, all the elkhorn coral at Guanahacabibes died. Now, crumbles of elkhorn limbs litter the sand. “There we are, we need to begin from zero again,” said Cuban coral scientist Pedro Chevalier.

For many coral experts, the Caribbean is a focal point because it has experienced the most catastrophic reef loss thus far. Bill Precht, a renowned coral scientist, said he sees value in the assisted sexual reproduction method, yet remains skeptical. Scientists involved in assisted sexual reproduction often try to capture spawn from parent colonies that appear resistant to heat stress. Sometimes, even when this is done successfully, said Precht, the water will get a bit hotter and everything will die anyway. “There’s a lot of papers that say, ‘oh, we’ve found it,’ ‘we’re finding it,’” he said. “But there’s no end of the rainbow yet.”

Miller is more hopeful. She knows larval propagation “is always going to take longer,” which is why she encourages the simultaneous use of many methods, including fragmentation. Bretos agrees, “The science is saying that sexual restoration has higher survivability and more scale but it’s not there yet, so we need both.”

Pedro Chevalier has been a leader in Cuban coral restoration for decades. He wants to help young Cubans fall in love with the undersea world, with the magic of coral reefs. But even if young people do become passionate about marine biology, many dream of leaving Cuba to find opportunities elsewhere – like many small island nations, Cuba suffers from persistent brain drain.

Between 2022 and 2023, over one million Cubans left the island, an estimated 10% of the total population. For Chevalier and Bretos, the coral restoration project has the potential to show young Cubans that there is work to be done protecting and restoring their natural world, right in their own backyard.

“This is a hope story,” Bretos said. “This is not a ‘look what we’ve done.’ This is a ‘look what we’re doing.’”

Chevalier worked at the National Aquarium of Cuba for nearly ten years. As part of a campaign of environmental education programs, they created a coral “garden” just off Havana. Here, they employ the asexual, fragmentation method of restoration. In a calm channel close to shore, divers bring strings of corals from the garden to the shallows where young children can interact with them. The children get to choose a fragment to name, and many pick based on colour or shape. The aquarium then posts photo updates of the growth of the juvenile corals on Facebook.

They’ll say, “‘Look, it’s my coral!’” said Chevalier. The aquarium staff have even had birthday parties for young corals with the children, who become just as excited about the science as the scientists themselves. They even bake cakes and desserts for the baby coral’s birthdays, celebrating the life they’ve helped nurture.

Whenever Chevalier talks about the kids and the corals, the skin around his eyes wrinkles and he grins. “Those kinds of people, children,” he said, “they love the sea.”